September 10, 2024

Interviewer: Uncle, I heard you used to build 吊脚楼 (diaojiaolou). Can you tell me about what it was like? These buildings are so rare nowadays.

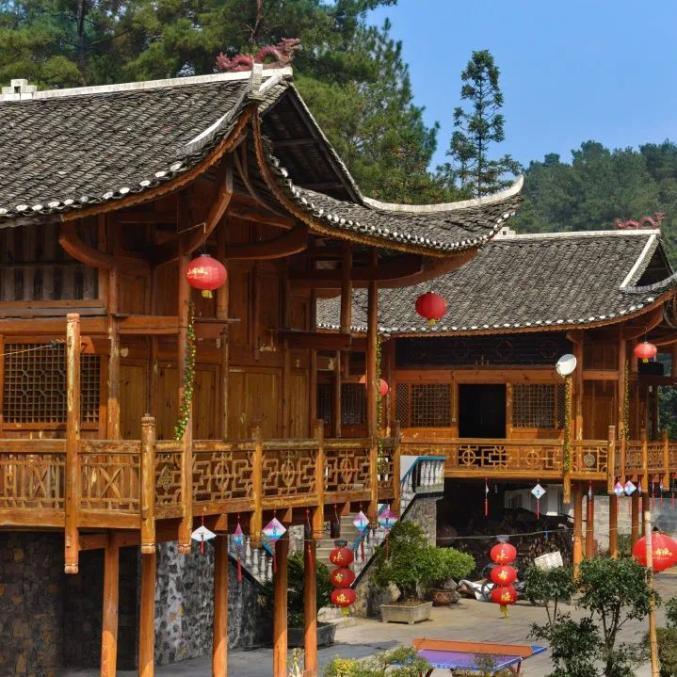

Uncle: (Scratches his chin, chuckling) Ah, those were the days, kid. Yeah, I used to build them. You’d see them all over the place back in the day, hanging right off the side of a mountain, like they were part of the landscape. 吊脚楼 were something special, built to fit the mountains, the rivers… everything. Now? (Shrugs) They’ve become relics, forgotten by most people.

Interviewer: What made them so special?

Uncle: They’re special ‘cause they weren’t just houses, they were part of the land, part of us. See, the 吊脚楼 wasn’t just thrown together. It was designed to adapt to the mountains, to let air in, to stay dry when it rained. The house would rest on those wooden stilts—干栏 we called it—so we could keep away from the snakes, the bugs, and whatever else was creeping around.

Interviewer: Well, can you walk me through how one was built? What was the process like?

Uncle: (Leans forward) Oh, it was no simple job, let me tell you. First, we’d have to find the right spot. Couldn’t just build anywhere—it had to be on the slope, overlooking water if possible, but stable. Then we’d gather the materials. The wood had to be perfect—tough enough to hold up, but not so heavy that it’d sink. My father taught me how to pick the right trees. We’d head into the forest, cut down the wood ourselves. You had to know which beams would be the stilts, which would form the skeleton of the house.

Once we had the wood, we’d start with the stilts. Those stilts—like legs—they’d be driven deep into the ground to create the foundation. We didn’t use nails, mind you. Everything was about fitting it together, piece by piece. The beams and columns interlocked like a puzzle—called it 穿斗式. It’s a flexible system, meant to handle the shifting ground, the earthquakes, all of it.

Then we’d build the walls, but they weren’t like today’s walls. They were thin, breathable. It’s hot and humid out here, so we needed those walls to let the air flow through. The roof, though? That’s where the real magic was. Deep eaves that stuck out far, angled just right to let the rain slide off without hitting the house. The roofs looked like they were flying, with those curves on the corners—like wings reaching out over the valley.

Interviewer: It sounds like every part had a reason.

Uncle: Oh, absolutely. Nothing was done by accident. Even the rooms themselves—they weren’t just thrown together. We had what we called 龛子, or the overhanging rooms, which hung out over the stilts. It was light, delicate work to make those rooms stand without toppling over. The details? (Chuckles) You wouldn’t believe the time we spent on the little carvings—the beams were decorated with birds, dragons, sometimes flowers. Each carving meant something: good luck, protection for the family, that sort of thing.

Interviewer: And what about the traditions behind them? Like, were there any ceremonies or customs when you finished building one?

Uncle: (Nods) Oh yeah, of course. When the house was finished, we’d have a whole celebration. The family would invite the whole village. We’d have a feast, music, dancing. But even before that, when we started laying the foundation, there were rituals. My father used to say a few words to the mountain, to the spirits, asking for permission to build. The 摆手堂 (the community hall) was another important part of our villages. Every time we built a 吊脚楼, it wasn’t just for the family—it was for the community. Our traditions are tied to those houses.

Interviewer: But why do you think people don’t build 吊脚楼 anymore?

Uncle: (Sighs) People just don’t appreciate the craft anymore. You see, building a 吊脚楼 wasn’t just about putting up a house. It was about working with the land, respecting it. We knew that the mountains were full of spirits—good and bad. The house had to live in harmony with the mountain, like it was part of it. These modern houses? They’re quick, cheap. People today don’t see the value in spending months building a home that’ll last generations. They want something now, something fast.

Interviewer: So, are 吊脚楼 really that different from buildings nowadays? How did you learn to build them?

Uncle: (Leans back, eyes gleaming) Oh, yeah, completely different. My old man taught me, and he learned from his father, and so on. You didn’t go to no school for it. You learned by watching, by doing. We’d wake up before dawn, grab our axes, and head up the mountain to find the right trees. Had to be good wood—strong, but light enough to balance on those stilts. The whole village would chip in, and when we finished, it wasn’t just a house. It was art, man. Every beam, every carving had a meaning.

Interviewer: You mentioned carvings. Were those important to the design?

Uncle: (Nods) Oh, absolutely. We’d carve birds, dragons, flowers—each one with its own story. Some of it was to protect the family, some just to show off the craftsmanship. (Laughs) It wasn’t just about building something to live in, it was about telling a story, connecting to the land, the ancestors, everything.

Interviewer: So why don’t people want that connection anymore?

Uncle: (Sighs, shaking his head) That’s the thing, isn’t it? People are too busy chasing money, trying to keep up with the world. They don’t see the value in what’s old. They think modern means better. But I tell you, these 吊脚楼… they breathed. They kept you cool in the summer, dry in the rain. And they were built to last, passed down from one generation to the next. It’s a damn shame, really. We’re losing more than just buildings. We’re losing our soul.

Interviewer: Do you ever miss building them?

Uncle: (Chuckles softly) Miss it? Sometimes. It’s special. There’s nothing like the smell of fresh wood, the sound of it fitting into place just right. And the feeling when you finish a house, standing there like it’s always been part of the mountain… you can’t beat that. But life moves on. Maybe someday people will come back to it, realize what they’ve lost. Until then, I’ve got my memories.

Interviewer: Do you think those traditions like this will survive?

Uncle: (Pauses, gazing out) I hope so. But it’s getting harder to see that happening. People don’t care about it as much as they used to. Back then, we had 摆手舞—that dance was everything. We’d all gather, men and women, and dance in front of the new house. It was like a way of saying thanks, a way of connecting with the ancestors and the spirits. Even the songs had meaning. But now? People don’t have time for that. The houses are gone, and with them, the traditions. But, hey, some of us still remember, and as long as we do, they’re not completely lost.

Interviewer: Thank you for sharing all this, Uncle. It’s important that we keep these stories alive.

Uncle: (Nods, smiling softly) Good (Pauses) I just hope someday folks realize what they’ve lost before it’s too late.